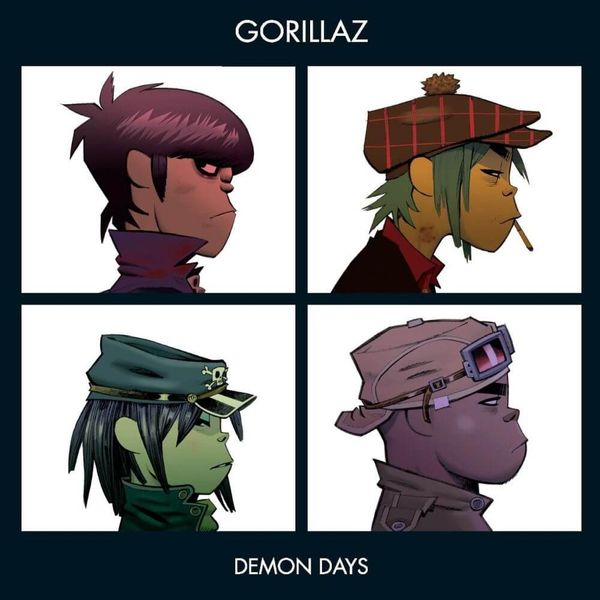

When is a virtual band over? That’s been the question on my mind since listening to Humanz, an album that confirmed fears which had been lurking since Plastic Beach. Gorillaz don’t seem to be a thing anymore. Albums have their name on them, the gang get wheeled out for interviews, but I don’t hear them in the music. It isn’t a novel feeling, obviously. Bands lose their spark all the time, but there’s something decidedly sinister about it happening to 2-D and the gang. Without the music belonging to them they’re nothing but cardboard cutouts, and without them the music rings hollow.

Gorillaz were the first band I really payed attention to, and I think that's true of a fair few people in my generation. I adored what they represented. They were a unique education in the potential of music to elevate, because they cut out the middlemen. There was the band, and there was the music — the people behind the music were utterly immaterial. No flawed, boring, disappointing humans redeemed by bursts of genius, just the genius. They represented the power of a band. A bunch of cartoon characters turn up and make some noise, and we love them for it. Not so different from a ‘real’ band. We don’t know the artists behind the records we love, we know the characters they play. Their work defined them. Gorillaz were such a pure representation of that image, and it resonated with people. They embodied the suspension of disbelief that allows us to latch onto the substance of what a performer is saying. Typically, Anthony Fantano summed it up nicely in his review of Humanz:

‘Gorillaz is about creating music for a band that doesn’t really exist. It’s about creating music that’s otherworldly, from a different place, and it’s so vibrant and creative and detailed that it feels real. Suspending that disbelief is part of what makes the project — and the band — so intriguing and entertaining.’

The visuals free Gorillaz of baggage, but the music is their lifeblood. When the music isn’t made for the band the members cease to exist, however strong the imagery is. Plastic Beach flirted with this problem; Humanz knocked it up. The overwhelming sense in our own review was one of alienation, of not hearing a Gorillaz album. It’s a common feeling. Jamie Hewlett, the artist behind Gorillaz, recently shared some the frustrations he felt during and after the creation of Plastic Beach:

‘Damon had half the Clash on stage, and Bobby Womack and Mos Def and De La Soul, and fucking Hypnotic Brass Ensemble and Bashy and everyone else. It was the greatest band ever. And the screen on stage behind them seemed to get smaller every day. I’d say, ‘Have we got a new screen?’ and the tour manager was like, ‘No, it’s the same screen.’ Because it seemed to me like it was getting smaller.’

The story’s telling, because the same effect can be heard in the music itself. Although Plastic Beach has its moments of synergy, where you could hear the band and believed they were there, it didn’t hold together like Demon Days, or even Gorillaz. The same deference wasn’t paid to the band. As an example, spot the difference in immersion between “Clint Eastwood” and “Welcome to the World of the Plastic Beach”.

Handpicked music videos aren’t proof of anything, obviously, but they are suggestive. One is the band wedding their sound with a collaborator who feels like he belongs in their harmonic world, the other is Snoop Dogg imitating Captain Pugwash. It’s a juxtaposition that tends to hold true. Post-Demon Days Gorillaz seem more like an outlet for Albarn’s whims than a force in their own right. The group don’t control the music. I’m not convinced 2-D’s singing, or that Murdoc’s defiling his bass, or that collaborators are ghosts bursting out of Russel’s drum kit and giant heads wired into Noodle’s sound system. I don’t believe it anymore.

And I welcome evolutions in sound. It’s healthy. But they all too often sound like Albarn’s, rather than Murdoc’s or Noodle’s. There are glimpses in Plastic Beach and Humanz of a developed identity; groovier, more modern, unquestionably Gorillaz, but they’re such a rarity that they seem accidental. It almost feels cheeky slapping the gang on the cover when they’re clearly bound and gagged in some shed somewhere. Albarn and Hewlett are already talking about another album, which I would love to be excited about, but I’m not. The deference paid to the Gorillaz ideal kept the music in check in spite of the number of collaborators, and the restraint isn’t there anymore. What will phase 5 look like? Rave music and Albarn beatboxing, with music videos of Murdoc dying of shock and spinning in his grave? It might be entertaining, it will push plenty of people’s buttons, but it won’t be Gorillaz.

In many respects this is appropriate. Bands evolve in sound, change their direction, lose direction, lose spark, announce themselves to new audiences as they lose connection with old ones. It’s natural, and the generally positive response to Humanz suggests there is a future for Gorillaz. What I find disappointing is that the journey doesn’t belong to the band anymore, it belongs to Albarn, and that’s likely how things will remain.